Simply Speaking with Albert Einstein

Years ago I was visiting a financial services regional office and conducting an informal “walk-through” prior to deciding on whether to pursue business development with them. This particular division serviced auto loans. As I went around the workstations I noticed a desk with a very large stack of mail, a very large stack. One individual was opening and sorting each envelope. I asked about it and was told that the individual was the accounting manager and they were the only person in the facility authorized to open incoming mail. I tried very hard to mask my reaction as I asked why that rule was in place. “Well, a few years ago we had an individual steal some money from a payment envelope, so we implemented this improved control so that never happens again.” Flashes of Humphrey Bogart and strawberries in the “Caine Mutiny” suddenly appeared.

I’m certain most of us have countless similar stories. I’ve long held that given enough time, today’s problems generate solutions that eventually become tomorrow’s problems. In fact, most controls have an inherent constraining dimension; they want to keep something from happening. When they are good controls, they attack the current causes and then adapt to changes in inputs or causes, but for many controls, not often enough. Controls become part of the paradigms of “how we do it around here.” Sadly, poor controls tend to punish the innocent in search of the guilty.

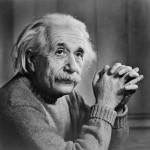

Albert Einstein is well known for his genius and insights into the nature of the cosmos. He cracked the nut around what gravity is, something Isaac Newton described as an attractive force, but could not explain. Genius notwithstanding, many of his enjoyable insights have survived in quotations that serve us well in life and business. Constraints that we encounter in our processes are often invisible to our eyes because they are consistent with the way we think or have been trained to see. We are empirical creatures who observe patterns and ascribe meaning to patterns. When we try something and it appears to work, we store that bit of information and draw upon it over and over. We call that knowledge and experience and it gives us and those around us comfort and confidence, even when that knowledge and experience is the cause of current calamities. Albert would say, “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.”

There is unquestionable merit in reducing unnecessary complexity and inappropriate controls in or work and lives. In fact, Albert would say, “Any intelligent fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent. It takes a touch of genius — and a lot of courage — to move in the opposite direction.” Many have assumed that simplification is the way to go. I’ve noticed a disturbing trend to make simplification the objective of improvement, potentially at the expense of quality and consequences. Years ago a good friend explained that where they grew up, calling someone “simple” was very uncomplimentary …. I understand why. Simplification does not mean simple.

Our auto loan example likely dealt with dishonest behavior, but at a huge price to flow and bandwidth. It did not address the root causes that were likely to be more complex and likely to emerge in other behaviors.

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”